Introduction

As I mentioned in my previous post, I recently went through the process of migrating one of our Azure Functions to .NET 6 and also took the opportunity to migrate it to run as an isolated process.

The process for performing this migration is not a well-documented one, and required a lot of google searches to get right. This post is my own contribution towards correcting this issue, and will hopefully find someone just at the right time. I won't spend any more time talking about Isolated Process functions, because if you have found this post you are probably aware of why you want to migrate to them.

Introducing our Example project

In order to make this a clear tutorial, I have provided a sample repository to show my working. This can be found here. If you would like to just see the finished product, you can just flip over to the branch named completed. The functions in our application are nothing special at all, and look like this:

public class GreeterFunctions

{

private readonly GreetingService _greetingService;

private readonly ILogger<GreeterFunctions> _logger;

public GreeterFunctions(GreetingService greetingService,

ILogger<GreeterFunctions> logger)

{

_greetingService = greetingService;

_logger = logger;

}

[FunctionName("http-greeter")]

public async Task<IActionResult> Greet(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "get", Route = "Greet/{name?}")]

HttpRequest req,

string name)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

{

_logger.LogError("Path parameter 'name' is missing.");

return new BadRequestResult();

}

return new OkObjectResult(await _greetingService.Greet(name));

}

[FunctionName("audit-greeting")]

public void Audit(

[QueueTrigger("audit-messages", Connection = "QueueConnectionString")]

string message)

{

_logger.LogTrace($"Greeting detected: {message}");

}

}

As you can see, it's a HTTP Trigger function that takes a name and returns a greeting, along with a Queue Trigger function that just logs the greeting. It doesn't have to be anything special, it just needs to be enough to demonstrate what we want to do.

First Steps

The first thing you need to do is update your AzureFunctionsVersion property in your csproj file to V4, and while we're at it we need to change our OutputType to Exe.

At this point, your project will no longer build. Don't panic, you just need to add a Program class with a static void Main method as the entrypoint to your application. This can be empty at this point, as it will be changing later. If you have made these changes correctly, the top section of your csproj file should look something like this:

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>net6.0</TargetFramework>

<AzureFunctionsVersion>V4</AzureFunctionsVersion>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

</PropertyGroup>

For the last part of this section, we need to change our FUNCTIONS_WORKER_RUNTIME app setting in local.settings.json to dotnet-isolated:

"FUNCTIONS_WORKER_RUNTIME": "dotnet-isolated",

If your function is hosted in Azure, which I'm assuming it is, you will also need to update your App Settings in Azure with this value, but if you're doing cloud infrastructure correctly in the first place this should be as simple as updating your ARM/Terraform templates.

Creating our Function Host

Now that our functions are running as a console application, we need to write our startup code to make the functions available to the host. In order to do this you will require three packages to be installed: Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Worker, Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Worker.Extensions.Abstractions and Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Worker.Sdk.

Now in our Program.cs file, delete everything and paste the following code:

using Microsoft.Extensions.Hosting;

var host = new HostBuilder()

.ConfigureFunctionsWorkerDefaults()

.Build();

await host.RunAsync();

If you've never used top level statements in C# before, this may seem a bit jarring. Basically, what this means is that the code we pasted in will be treated by the compiler as our Main method. This means writing less boilerplate code, and most importantly it means our entrypoint to the application can use async/await!

Dependency Injection

If you've ever implemented dependency injection into a Function app before, you've probably had to create a class that looks like this:

public class Startup : FunctionsStartup

{

public override void Configure(IFunctionsHostBuilder builder)

{

builder.Services.AddScoped<GreetingService>();

builder.Services.AddScoped<QueueService>();

builder.Services.Configure<QueueSettings>(options =>

{

var environmentVariables = Environment.GetEnvironmentVariables();

var connectionString = environmentVariables["QueueConnectionString"]?.ToString();

var queueName = environmentVariables["QueueName"]?.ToString();

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(connectionString) || string.IsNullOrEmpty(queueName))

{

throw new ApplicationException("Function cannot start without valid settings for queue storage.");

}

options.ConnectionString = connectionString;

options.QueueName = queueName;

});

}

}

It works fine enough, but by running our Function app as an isolated process, we are able to do dependency injection just like we would in ASP.NET Core! In our Program.cs file, we just need to add a call to the ConfigureServices method on our host builder:

var host = new HostBuilder()

.ConfigureFunctionsWorkerDefaults()

.ConfigureServices(services =>

{

services.AddScoped<GreetingService>();

services.AddScoped<QueueService>();

services.Configure<QueueSettings>(options =>

{

var environmentVariables = Environment.GetEnvironmentVariables();

var connectionString = environmentVariables["QueueConnectionString"]?.ToString();

var queueName = environmentVariables["QueueName"]?.ToString();

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(connectionString) || string.IsNullOrEmpty(queueName))

{

throw new ApplicationException("Function cannot start without valid settings for queue storage.");

}

options.ConnectionString = connectionString;

options.QueueName = queueName;

});

})

.Build();

At this point, we're at the point of no return, so lets go ahead and remove any package references to Azure Functions or WebJobs that don't include the term Worker. Our Function app will no longer build, but don't panic because we're just about to fix it! While we're at it, feel free to delete your Startup class now that we've moved our Dependency Injection to the Program.cs file.

Rebuilding our HTTP Trigger Function

The first thing we need to do is install the package Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Worker.Extensions.Http, which will give us access to the types required by our HTTP Trigger function. You will see that IActionResult and HttpRequest are now glowing red because the IDE doesn't know what these types are anymore. To make this concise, please make the following changes:

Change

HttpRequesttoHttpRequestDataChange

IActionResulttoHttpResponseDataChange

FunctionNametoFunction

This means our HTTP function now looks like this:

[Function("http-greeter")]

public async Task<HttpResponseData> Greet(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "get", Route = "Greet/{name?}")]

HttpRequestData req,

string name)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

{

_logger.LogError("Path parameter 'name' is missing.");

return new BadRequestResult();

}

return new OkObjectResult(await _greetingService.Greet(name));

}

You'll notice that the application still won't build because it's trying to return an value of IActionResult instead of HttpResponseData. Starting with our BadRequest, we change this to:

return req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.BadRequest);

And now for our OK response:

var response = req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK);

await response.WriteStringAsync(await _greetingService.Greet(name));

return response;

Now the finished product should look like this:

[Function("http-greeter")]

public async Task<HttpResponseData> Greet(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Function, "get", Route = "Greet/{name?}")]

HttpRequestData req,

string name)

{

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

{

_logger.LogError("Path parameter 'name' is missing.");

return req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.BadRequest);

}

var response = req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK);

await response.WriteStringAsync(await _greetingService.Greet(name));

return response;

}

Rebuilding our Queue Trigger Function

Just like the HTTP Trigger Function, we need to start by installing the appropriate package to allow us to work with Queue Storage. This package is Microsoft.Azure.Functions.Worker.Extensions.Storage.Queues, and in a helpful twist introduces no breaking changes.

Presuming you already changed your FunctionName to Function earlier, your finished function should look like this:

[Function("audit-greeting")]

public void Audit(

[QueueTrigger("audit-messages", Connection = "QueueConnectionString")]

string message)

{

_logger.LogTrace($"Greeting detected: {message}");

}

Running the Functions

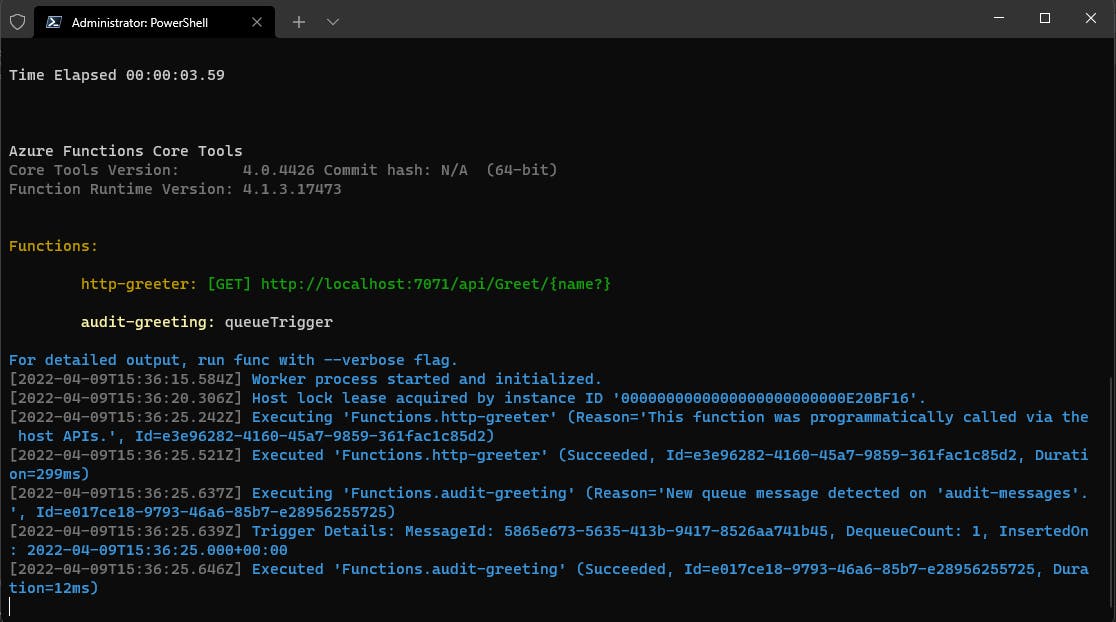

Now that we've migrated our functions over, it's time to run them to see if everything works! For whatever reason, Rider doesn't like running these isolated-process functions so I run them using the Azure Functions Core Tools from Microsoft.

To run via the command-line you go to the directory containing your Program.cs file and run func start. That's it, and you should be presented with a screen looking like this:

If you get this far, it's pretty much done!

Final Thoughts

While this blog post made it seem quite easy, I feel that Microsoft made finding this information far more difficult than it should have been. This, coupled with the lack of IDE support for this new hosting model made for a frustrating process, but we got there in the end.

Something you should know about this hosting model is that cold start times are longer, and it is recommended that you run on a Linux host. If this added latency is a big issue for your use-case I would strongly recommend staying on the in-process hosting model, which is also available in .NET 6.

If you would like to know more about the benefits of running your functions as an isolated process, I'd recommend consulting the Microsoft Docs on the subject.